These Lives

I want to hear about the ones who died,

And why with trembling hand and chin,

You hide behind the smile,

That brought tears to your mother's eye when you were born.

I want you to know how by street lamp light,

Your face adorned in ghostly glow,

I imagine there was a time,

Or will be then,

We knew each other as those for whom the story goes,

The clock would not divide.

I want to tell you,

I've tried to cry,

And failing that, saved all of it for one split second,

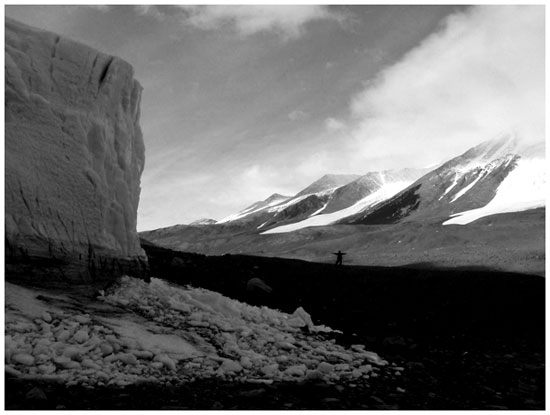

Upon an ice clad hill so far away no one could hear,

Shouted to God to forgive such ignorance,

Or punish me with an answer,

And heard only million-year old wind.

I want to tell you this isn't a love poem,

But that which by the will of he who made me,

Requires by my hand to make from nothing,

What I can image from deep within,

The wake from where I've been,

And live no more.

my diary, Hughes Glacier, 2001

In 1996 Hurricane Fran flew over Cary, North Carolina on its way to certain death in the north Atlantic. Cary is so far inland they rarely make hurricane preparations. It had been fifty years since the last hurricane went through, and that one was a wimp.

Fran was force one when the eyewall went over my house in the dark gray haze at three in the morning. Sustained winds were in the eighties's of miles per hour. Gusts got to one-hundred ten. You have trouble standing in an eighty mile-per-hour wind, and you certainly can't in one-hundred ten.

We brought the children to the center of the house were there were no windows. They slept on the floor in the little sleeping bags we'd bought them to use when they went to pyjama parties. They thought it was fun to sleep by candle light.

I watched them sleep. I sat next to my wife keeping vigil, telling the kids to go back to sleep when the giant oaks fell and the thump of their trunks against the ground made earthquakes. We told them to go back to sleep when the tornado thundered past, a train off its tracks, howling like a disembodied spirit screaming through the long tube between life and death.

I couldn't protect them. I waited for the roof to fall in on us, and I knew I would throw myself over them at the first sign of cracking. I would try to die first.

The barometer needle dropped. The shrill wind drowned our inside voices. We could speak only in screams.

You can't run from a hurricane. You can get in your car and try to ford the flash floods and the tree limbs hurtling like artillery, but you have to make it for hundreds of miles, and you won't make it.

You can't escape the floods underground. The winds will destroy your flimsy wood home. Flip your car.

Across the street the pines had fallen into the houses. One had cut a slice through the Blum's two story home. It ripped a slit from the apex of the roof to the foundation. Mr. Blum fought to put a tarp over the gash. The wind took the tarp and Mr. Blum fell from the ladder. I was going to run out to help him, but he managed to get up and get back into his broken home.

We shone flashlights at each other across the road. Blinked them like "Victory at Sea". If only we could figure out how to make the blinks mean something.

When the sun rose and the winds died, I left my home in living color to step, reverse-Dorothy, into black and white.

Our neighborhood was destroyed. Homes in pieces. Roofs torn off. Entire sections crushed by trees. Cars flattened. Roads impassable, criss-crossed by five-ton tree trunks.

The horizon was different. Our little hamlet in the forest was now a broken village on a flattened battlefield.

I climbed over the tree trunks and stood in the center of my street, not knowing what to do. In the distance there was movement. Something sky blue, someone sky blue climbing over the fallen trees.

Doc Wheeler was in his hospital scrubs. We stood among the wreckage. It felt like the end of the world.

"We should see if anyone's hurt," he said. "You all okay?"

I told him we were. Our house had been spared major damage. All souls well.

"Good. We're okay, too," he said. "Let's go now and see if anyone needs our help."

He said, "our help," as if there was something I could do for anyone hurt in the disaster.

The night before my dad died he fell trying to get out of bed to go to the bathroom. The cancer ate him so bad his legs didn't work anymore, but he was stubborn. The last shred of any man's dignity is in being able to make it to the toilet alone.

And he fell on the two yards of carpet between the edge of the mattress and the bathroom door.

I had been staying in the bedroom that used to be my sisters', sleeping on one of the old beds too small for a six-foot man, so my feet hung in space off the back of the mattress. I didn't realize it was a loud thump that woke me up. Sleep had gone so fast I scanned through my dream memory like it was real life.

Then I heard the groan and I ran to his bedroom.

Without my glasses all I could see in the blue-white moonlight was something child-sized writhing on the floor like a creature from a Lovecraft horror, or a character from the X-files come to haunt my waking nightmare.

But I didn't stop. Sheer momentum brought me to it. I slipped my arms under it, Pulled it slowly, shaking, to its feet.

It was like a baby bird, trembling, a loose collection of bones draped in thin skin, tiny bits of life clinging to it like melting snowflakes.

The strongest man I knew said, "Look what's become of me."

I helped him into the bathroom. I lifted the toilet seat for him, and held him while he peed.

In my mind the words, "This is the man who is responsible for my life. This is the man who built my bicycles on Christmas morning. This is the man who nearly got into a car crash racing to the hospital so he could be the first to see my newborn daughter."

And in that yellow sixty-watt incandescent tiled daytime I wanted burn down the house. I wanted him to die so he wasn't that way anymore. I wanted to crash my cars and blow up the Brooklyn bridge.

When I got him back in his bed he said, "This life, Joey..."

Then the drugs knocked him out. But I was full of hurricane, the pungent spray of sap from shattered trees, blood from the splinters, fear of the falling night sky.

Because I could not forget there is no help, I did not sleep for days.

We walked through the valley, alone for hundreds of miles, a prehistoric landscape visited by so few people there were no footprints on the soft still earth. Around us the ground was scarred in frost heave's deep polygonal grooves outlined in white traces of snow.

She had grown up in poverty. Lived in doorways. Abandoned cars. School busses. The only time she'd showered or bathed was when a school friend invited her home, and the parents insisted. Somehow she was smart enough to finish school. College. Land a job with a major newspaper, and then a well-known magazine.

She had money, but no use for it.

Now we were both in Antarctica, hiking the Taylor valley, taking pictures, her for her major magazine, me for myself, my kids, anyone who would look.

"The whole northern hemisphere could disappear in nuclear war and we'd never know," she said.

I snapped a couple of pictures, trying to keep myself from imagining a horror my family could endure without me. No--if there was going to be a nuclear cataclysm, I'd be best off evaporating with my wife and kids than hiding out at the bottom of the earth.

"What a life," she said, stepping onto a boulder the size of a small car. "You come here, you feel just like a kid again."

"All this is here whether we are or not," I said gesturing to the glaciers, the ventifact stones, the frozen lakes, imagining I'd said something profound. But she squinted when she looked at me, and so I know I was missing her point.

"You know how many people in the history of the world have been here?" she asked.

"Not many."

"You can count them. They're all numbered. We know who they are from the time Scott first discovered this place to now."

"Cool," I said, or something equally unattentive.

"Do you know what it's like growing up with nothing?"

I told her I didn't. We weren't rich, but we had things. Always.

"Of course you did," she said. Then she started walking. I followed her in silence for about a half a mile, not wanting to disturb her. Something had struck a nerve, and I was hoping it wasn't me. I had a good childhood. Considered myself successful. Maybe that was getting to her.

When we got to the base of an ancient blue ice glacier she stopped and stared.

"When I was young, I never knew we were poor. I thought everyone lived like we did. I never felt I was missing anything until I grew up and saw how other people lived. Then I wanted clothes and toys and my own bedroom."

I lifted my camera. I wanted to be as quiet as a stone. I wanted to be ice.

She took pictures of the miraculous nothing of everything around us.

"You might feel lost, but you never are. You have everything, you know?" she said, taking my picture against the backdrop of the void from which we would never return.

The first time I saw the woman I married, I knew I would.

I was seventeen, drinking underage in a sleazy dive called "Down the Hatch" in Highlands, New Jersey.

There was a band playing. The song was Getting better, by the Beatles.

She walked in with a friend who recognized the guy I was with. We were trying to be inconspicuous, gleefully swilling ilicit light beers in a dark corner.

The women came over to us. We bought them beers because their fake ID wasn't as irrefutable as ours. We drank and talked about going dancing.

I couldn't take my eyes off her. When she looked at me I saw my whole future. I smelled baking bread and saw Christmas tree lights. I poked myself with baby diaper pins. I bought her glasses of chardonnay and drove her to surprise parties.

She tried to teach me to dance, but I was hopeless. She laughed at me on the blonde hardwood floor, the band playing song after song while I sweat rivers trying to mimic her steps, moving like an ostrich shot in the foot.

I wrote her love poems. I wrote her stories. When she was gone I ached for her and music came out my fingers.

I wrote our wedding song and coached the band we'd hired how to play it "right".

We've been together twenty years. I've seen every line on her face form and deepen. I've seen her crying in pain giving birth. Spent days in hospitals with her, surgery upon surgery. We've bought houses together. Driven through deserts. Hurt each other. Tried all the sex we could imagine. Sat through endless weddings together, funerals for countless family members and a couple of close friends.

I know the smell of her breath at midnight. When I press my ear to the mattress, I hear her heartbeat.

"Did you ever think it would turn out like this?" I asked her at breakfast. The kids were out of earshot. They had scarfed down their yogurt and orange juice and were collecting their books for school.

My wife got worried. That was the kind of question a husband asks from deep within a mid-life crisis, right before he runs away with the 25-year old blonde who can't tell you the name of Jimmy Carter's vice president.

She scowled for a minute. "You know, it's never any different."

I said, "When I was a kid there was this song, 'What's it All About, Alfie?' It was on the radio all the time. It was my mom and dad's theme song. Everytime something disappointing would happen, my dad would lose a job or something expensive would break in the house, my dad's moment of philosophical introspection was to look at the sky and say, 'What's it all about, Alfie?'"

My wife drank her coffee and went back to her crossword puzzle. She'd heard a variety of versions of this story for most of our life together.

"But then he died," I said, trying to figure out what I was feeling, how to say it, and whether it was worth the trouble. It took a few seconds of listening to the kids rattling around in the hallway, pushing and shoving each other on their way out the door to school. I wanted to complete the thought.

She already knew I didn't want to be like him, and that I was afraid I couldn't help it.

"I don't think he ever figured it out."

Every night, before she goes to bed, my youngest daughter finds me and kisses me goodnight.

The other kids gave up the practice when they got older. This one, almost a teenager, never did.

No matter where I am or what I'm doing, she waits until she can come to me quietly, and says goodnight, and kisses me on the cheek.

"Goodnight daddy."

"Goodnight sweet pea."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home