Purgatory

My country is at war. With itself.

It is a terrible war that turns brother against brother, that turns truth into concept at the speed of thought. It comes complete with computer graphics, rendering and theme music. If the cold war were still on, we'd blame the Communists for the divide.

Maybe it is.

I don't know where it started. I think the most brazen activities were probably initiated during the Clinton administration where the American populace was shocked to know our president would dare to suggest we didn't understand the definition of the two-letter word, "is". As shocked as we could be, nothing could have prepared us for the onslaught we are forced to withstand day after day as our politicians and their paid media minions write history in pencil then erase and rewrite it to their individual profit.

We have managed to convince ourselves we are in living in a time that demands the uprooting of our most closely held values as citizens and even as human beings. Our leaders feed us barely hidden lies to get us to follow them, and then wink snidely as if to let us know we're all in on the joke. The lie is that we need to unhinge 200 years of law. The lie is that our Constitution and 200 years of judgment is faulty.

Technology allows this cooperative deception to occur on a massive scale. We are fed bullshit through computer networks and cable television that are free from the restrictions of decency imposed by the archaic rules mandated by the government who limits itself to protecting only the free airwaves.

And consequently we are manipulated by tiny vicious men who send our children into war to do their bidding. And we don't care.

We get what we deserve. America is crumbling. What will fill the vacuum that is left by the implosion of the last great bastion of the free and brave? Who will stand in our place? Lucky for our former allies, we've relegated them to the sidelines, and they'll watch in horror as the giant whirlpool takes us all down into the sewer of history. And then they'll go about their lives.

I have ceased to be amazed that rational people are willing to believe what they're told in print and by shining spots on screens before their eyes. I have ceased to be amazed that people can continue to believe a lie after it has been uncovered before their very eyes like an audience who insists there are ghosts even after the magician has showed us the mirror and the smoke machine.

We are getting what the majority wants: a choice between the agonizing death of a thousand cuts, or the life-crushing pain of untreated cancer, all because we'd rather believe the screen than our eyes.

I want to believe a change of political party will cure my country. But it won't. We'll replace one set of corrupt, self-serving ideologues for another.

There is no hope but for people to turn of their computers and televisions and look into their own hearts.

And Rupert Murdock will never allow that to happen.

We are the TV generation. It is our true God. And God is selling our souls into slavery.

The Alaskan Panhandle is known to all as Southeast Alaska and abbreviated to "Southeast" by residents in speech. Southeast is a different country than the interior, which is again a different country from the Aleutian chain, over 1500 miles to the west. Due to spherical geography Alaska spans as many degrees of longitude as the continental 48 states. Due to political edict Alaska comprises a single time zone to the four in the lower 48. Our clocks in Juneau are set to the same time as those in Adik, even though they're 50 degrees of longitude to our west. Imagine New York and Los Angeles having their clocks set identically instead of 3 hours apart.

Almost nobody lives in Alaska. There's not a lot of concern about the sun rising at three in the morning and setting at ten AM in Okmok. It makes things easier for people elsewhere, which is how things are in Alaska: easier for everyone else.

We are into the rainy season in Southeast. Natives are used to the sun disappearing behind the clouds at this time of year. It's not supposed to be sunny in the "ber" months. It adds to the gloom as we lose four minutes of daylight with each 24-hour cycle. It seems we have gone from daylight for all our waking hours to a sunlight rationing system.

The tea-colored muskeg puddles fill faster than they drain. The streets glisten perpetually. The air is dense with fog and raindrops.

"What is your favorite water?" the question goes.

Insects have all drowned.

"What is your favorite animal?"

The bears have all found their sleeping places.

"What's the difference between a brown bear and a grizzly?"

Free. Wild. Nothing. How did you kill your last insect?

Yesterday, the last cruise ship of the season came and left. Now the ship dock will be empty for six months and I will no longer have to give directions to the Greek Orthodox church or the State Assembly chambers to people whose maps are too wet and crumpled to use.

We are once again in self-imposed isolation. Rain pelts us ceaselessly. Ravens practice their ten different calls.

Are you a Republican, or are you a Democrat?

Raven's wings sound like ropes whistling through the wind. When they pass you swear a bullwhip flicked past your ear or the sails were lifted on a distant schooner. They represent a deity to the Southeast natives. One out of many.

Clever Raven created the world. Bald eagle is a vacuous beauty, concerned more with looks than substance.

There was no rain the year I moved to California from New Jersey. We could only wash our cars on alternate Sundays. It was illegal to water the lawn.

Every day the sun sailed across cloudless blue. Every night the high fog clotted and formed a billowing ceiling that reflected our sodium lamps. In the morning it melted to blue clarity.

Free under the blue infinity, Californians will try anything.

People are cautious where the weather changes. In New Jersey, bad luck hides like a wolf in the brush, waiting to pounce upon the brave and the unaware.

"That's how they get you," my father used to say. It was a multi-purpose phrase.

As far as he was concerned there was a reason, a victim, and a guilty party to every misfortune on earth.

His phrase is suitably followed with: "I hate them for that reason."

There was the story of the man who broke down on Route 46, on the bridge that went over another highway, Route 1. It's an old two lane bridge. There's no shoulder, and only an old ivory-colored concrete barrier between the bridge surface and the roadway below. He set out flares and reflectors and parked as far to the right as he could, but eventually someone wasn't going to stop.

A tractor trailer did not stop. There was no place for the motorist to go to avoid the accident. Seconds before the truck collided into his stalled car at highway speed the man leapt from the bridge - and broke both legs in awful spiral fractures when he hit the route 1 fast lane on both feet.

His legs demolished, he had to crawl to the shoulder of the road on his elbows before the light changed and the traffic resumed and crushed him. And he as he started his crawl his broken car was hurled off the bridge by the collision with the truck. It hit behind him at the spot he'd just left while he slithered on his elbows.

What a bad day.

"That's how they get you," Dad said about the truck crash. "They never slow down. Not for any reason. I hate them for that reason."

"Far be it for me to be a ray of sunshine, but maybe the guy was totally lucky. He lived."

"Luck would have been not having a piece of shit car that breaks down on an overpass."

Luck would be having a better paying job and a career that led to a bright future instead of driving a Plymouth Dart with a leaky carburetor float. Luck would be living in a 6-bedroom home with a gated yard and a gardener named Luis who'd be appreciative for big tips come Christmas time. Luck would be owning a fractional Gulfstream IV.

Because we didn't have a jet, we'd be prey to those out to get us. And they were. And we would be got. And we would hate them for it.

"That's how they get you."

"You hate them for that reason."

"Yes. I do. You have anything else to say, smartass?"

"Nope. Not me."

How you answer to water is your subconscious preference for sex.

How you answer to animals is your subconscious preference for friends.

How you answer to killing insects is your subconscious preference for handling difficult situations.

How you answer to Republican or Democrat is your subconscious desire to please your parents.

Does God want us to be cautious, or carefree? Do you live in the sun or the rain?

We ask this way because you can't answer a direct question. Because everything means something, which is something else.

I can't help but think in this endless Southeast rain

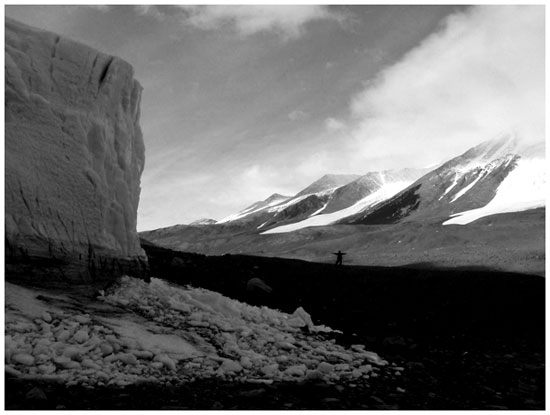

of everyone who died who loved me. You have, in purgatory, only the hope you have brought with you. There is no sun I'll see again until I am forgiven my sins by those who no longer have a voice here. The resurrection of the dead. The return of the spirit.

On track, the motel rug

I pace step after step

As if I was anywhere

We could be anywhere

I have been anyone

A businessman killing time

A musician not sleeping midday

Wringing my hands

It's always too early for the show.

My father was a Democrat, but he might have become a Republican had he survived. He would have enjoyed the demonization of strangers and random events. There were times that having someone to hate gave him purpose.

It would never have occurred to him that taking fate from God and handing it to the Devil turned his world into purgatory, and that he could change it by refusing to strike our when his luck turned sour.

The formula is that anger is a release for the frustration we have built wishing we had when we don't. We are sold on the idea our lives will improve by patronizing the advertisers. Because we measure our happiness in terms relative to those around us, we can only "feel" the changes in our lives. So we must continue to patronize the advertisers. And when we have built up a high enough tolerance for that drug, we turn our efforts against ourselves. Then the politicians give us the chance to free ourselves from self-loathing by channeling our frustration into fear and hatred.

So that they can patronize the advertisers.

That's how they get you.

That's how they make you hate.