Gjelder Hele Svalbard

We can't fight the isbjornen on their terms, so we carry Rugers and Marlins. Signs on the street warn us this territory isn't fully under the control of the human species. The brochures suggest we carry nothing smaller than a .450 Marlin. The .458 Winchester is preferable. Nothing smaller than a 12-gauge slug gun if you prefer the smooth bore. Ten gauge is the better bet. SKS assault weapons aren't recommended but they're in the gun case at the hotel.

Signs in the butikken remind us to check our weapons at the door. The grocery aisles are free of carnivorous predators. Here we have subjugated other species: relegated them to cutlets to provide us protein. Here lie the swine, the crab, the hvalbif.

"Hvalbif?" says the blonde haired girl. She hefts the vacuum packed chunk, red purple like a palm-sized blood clot.

The Lonely Planet guide to Scandinavia provides me the English translation, which like most Scandinavian translations is more like a change of accent than a contextual recoding.

I say, "Sound it out," and she stands lip syncing to the word in her head.

"Hvalbif. I don't get it."

"For instance, to the bears we're boybif and girlbif."

The guy at the coffee shop tells us the score. Much easier to get a high powered weapon than rent a vehicle. At least you've paid for the ammo and one way or another they'll get the gun back, is the thinking.

He says, "You should practice shooting, of course, before you leave town. Just to make sure you can work it. People get scared and shoot nothing."

"Where do you practice?"

He raises an eyebrow.

"I mean, can you just shoot anywhere?"

With the look of an amateur trying to decode hieroglyphics he says, "But not toward the people, of course."

"Sure but what if I decide not to take a gun? Wouldn't that just be safer?"

"Why?"

"Because they're dangerous?"

"Well it's okay. Anyway it's your life. We haven't had anyone attacked by bear for at least five years. Except for a woman last week but she wasn't in town. She was over on the hilltop, unarmed. Against strong advisement."

"Which hilltop?"

"That one."

"The one by the church parking lot?"

"Yeh."

"And how badly was she hurt?"

"Well absolutely killed, of course. Did you want anything on this coffee? Perhaps chocolate?"

Longyearbyen is further north than McMurdo station is south. The t-shirts in the duty free shops remind us we are north seventy eight degrees, thirteen minutes. Plow a road and you could be at the pole in a seven hour drive. Twelve by snowmobile, if you can possibly rent one instead of a rifle. The capital of Svalbard doesn't look much different than McMurdo. Sans volcano there are the same mountain ranges, the same sea channels, the same hyper-insulated buildings and dirt roads. But upon slightly closer inspection mighty differences emerge. One difference is you don't have to go to survival school to stay at the SAS Radisson Polar Hotel. Another difference is you take your shoes off when wandering inside. Nobody checks to see if you're cold in Svalbard. There are daycare centers and grammar school yards replete with kids dressed in inches of insulation playing tag under the seething aurora.

The school yards are surrounded by fences. Parents stand outside waiting for the bell to ring and the kids to be released.

"Do these fences keep out the bears?" we ask one of the mothers who has taken an interest in we rare polar winter tourists. Who comes to Svalbard in the 24-hour darkness?

Crazy people asking about polar bears.

"No bears come into town."

"But if they did, do these fences keep them out?"

"But we shoot them first so we don't worry."

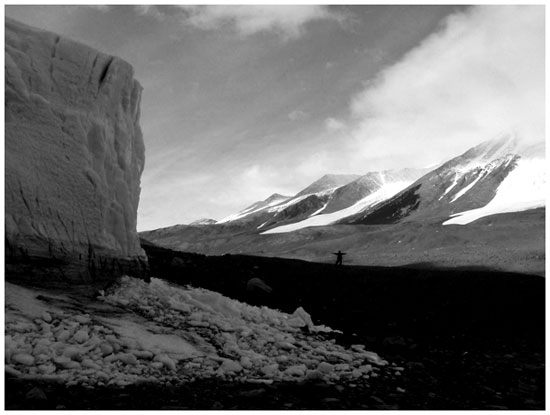

We walk down the road to the channel, and then up toward the peaks, toward what appears to be nowhere in polar terms. There is a yellowish blue stain on the horizon through which it's hard to see stars. The glow illuminates the snowy land pierced by stark black mountains draped in ice.

Eventually we come to a sign. It's a triangular pictogram, edged in red, rounded corners, black inside and stamped with a white iconic ursine form.

"So there is an international symbol for 'polar bear,'" I say to the blonde haired girl. "What do you think the words say?"

She doesn't know.

Later we find out it means "True in force all over Svalbard."

The wind bites into our thick clothing and wedges into a gap I hadn't seen when I got dressed. I pull my balaclava up over my nose which I learned in Antarctica was one of the most frostbite-prone areas on the human body.

And unlike Antarctica we have not had to get approval from any agency to walk down this road. And no one has had to make sure we're well-enough equipped. This is Norway where everyone is responsible for himself, and not only is it not the duty of those in charge to see to our safety, but they feel they would be insulting us if they did.

The natives must think we're daft. We're passed by a guy on a snowmobile, who must not be Norwegian because he slows and points to the sling on his shoulder, then takes off at speed. The dark metal melts into the night and it isn't until his red taillight fades to a point that I realize what he means.

"I would have gone for the Winchester," I say. "We should have shot at some of that driftwood for practice."

"But they were closed," she says. "And I'm not sitting around all weekend waiting for them to open. How often do you find yourself on Spitzbergen that you want to sit around a hotel room?"

"Aren't you interested to see what's on TV in Svalbard?"

She doesn't dignify the question. So I say, "Well, anyway, I probably wouldn't even see a polar bear in this gloom until it was too late. Damned isbjorn could drop down from one of these hills in a few seconds. We'd probably wind up shooting each other."

We walk until we realize the only reason we're not shivering is because we're walking. Then we head back toward the man-made yellow glow.

And on the high-cost tourist treks the guides do not insult you by making sure you have prepared appropriately for your adventure experience. If you are not dressed well, you will freeze. If you have not eaten you will starve. If you are thirsty you will dessicate. Proficiency is presumed. Incompetence is a surprise and upon encountering it they will do their best to keep the polar-challenged from dying, but this will detract from the experience of the others on the trek.

So when one on our dog sledding party discovered she was plunging into hypothermia half way through our trip toward the glacier, the guide simply pulled off one of his clothing layers and gave it to her.

"But now he's missing a coat," I said to the blond haired girl.

"He must be used to it."

"But it's minus twenty."

"But he gave her his coat. He must know."

"Do you think he'll freeze? He's got the gun."

"Maybe you don't freeze if you're from here."

"All human flesh freezes at the same temperature."

"What do you want me to say?"

"These Norwegians are very hearty people."

"They are hearty."

And when the brochure says: "You will have the experience of dog sledding, from choosing your dog to mushing across the tundras," they mean that you should be ready to go to the kennel and take the animal from its house and lash it to the harness.

Have you never been dog sledding? Then you will learn how this is done. You will learn how not to be bitten, which is to stay away from the mouth.

Our guide is Ivan. He says, "The first 400 meters out of the kennel are the hardest. There is a steep drop and a turn to the left. There is the feeling of falling off your sledge so do not fall off."

"What happens if I fall off?" I ask Ivan. I was born one to fall off things. It took me twenty years to learn to ski. I am certain I will not become a musher in my first 400 meters.

"You will then try not to fall off. This is the strong advisement. Please do not fall off. It is very difficult because once the dogs sense there is no person controlling them, they show the tendency to run very fast away from everyone. And of course it is night and there are bears."

"But if I fall off you can get the dogs back, right?"

"With some difficulty, this can be done. But I advise you to not fall off and it will be okay. And if you fall off you will not let go of the sledge no matter what. Please- no letting go." The LED lamp on his head needs no adjustment but he moves it anyway, and in doing so causes my unconscious headlamp check. My light is pointing toward the constellation of Orion and not toward anything that needs to be visible to an amateur musher. This I fix.

I mount the sledge the way I have been shown - one foot on the runner, one on the brake. I'm wearing mittens over my glove liners, so gripping the sledge handle requires more force than I expect.

The dogs howl and yap the way my neighbor's dog did before it died of heartworm. The dogs who have been left at their little dog houses in the snow join in the chorus. Ivan says, "They know what is going on and that they are not picked."

"Poor doggies," I say, suggesting I should have more than six of them lashed to my sledge. These are little guys compared to the 120-pound Akita I have at home. They don't weigh more than 30 pounds each and look emaciated. I wonder how they could pull a que ball across a billiard table. Ivan says, "Don't worry, it's enough," and his sledge begins to move. When my dogs see the lead sledge take off, they lunge forward against their harnesses and even with all my weight on the snow brake the contraption lurches.

I ease up on the brake and we begin to move smoothly out of the kennel gate and toward the open expanse of arctic twilight beyond, but immediately my lead dog disappears over what I discover to be a small cliff. With pressure on the brake I head over behind them, worrying all the time that with my mass combined with that of the sledge I outweigh the small dogs by over two times, and if I gather momentum I will pass them and this is not a cartoon and dragging the dogs downhill will be some degree of inadvisable badness I am unwilling to withstand. So I am hard on the brake and apologizing to those tiny creatures who are pulling so hard -

"I'm sorry doggies. You don't have to pull so hard because I have the brake on."

God has blessed the simple creatures with the lack of a cerebral cortex, so they have no means to become resentful and follow only their instinct, which is to pull until they die.

The trail curves hard left while we are descending. On the off camber turn my uphill runner tips and loses contact with the snow.

I shift my weight and concentrate on not falling.

And I do not fall.

Later, however, when I am not concentrating I do fall but I do not let go of the sledge and manage to drag myself back onto the moving runners like a hobo mounting an empty train car.

And even later, on the way back I fall off the sledge and lose my grip on a steep downward slope. As I roll to a stop I see my dogs accelerating forward, enjoying the sudden lack of an extra hundred kilos.

So I start screaming because I remember the woman who was absolutely killed for not following the advice, and I'm trying to move forward in the fading twilight, in a polar valley thousands of miles from my warm California home, surrounded by polar bears who haven't eaten in weeks -- aye, the females hibernate but the males hunt all winter -- unarmed in snow up to my knees, unclear which direction is the right one except to follow the sled tracks in the never ending darkness, night blind since laser surgery, frigid Svalbardian air seeping through the gap between my wind pants and parka, having forgotten nearly all of my Antarctic survival training (does it even work in the arctic?) --

this is an appropriate way for me to die, I suspect. If they had asked me before birth: "How do you want to go out?"

"What are my choices?"

"Well, there's cancer. Heart attack. Dementia, maybe accidentally eat rat poison. Violent crime. Air crash. Losing your dog sled in the Bolterdalen valley and freezing/being eaten by polar bears. Auto accident. That kind of thing."

"Are there other choices?"

"Many."

"I kind of like the dog sledding idea. It's unique."

"Very creative. Shall we put you down?"

"Please."

But I do not die in the Bolterdalen valley.

Instead, Ivan stops my dog sled somewhere far from where I have come to rest on the hillside. And because he is Norwegian and this is not a vacation for sissies who want to see Mickey Mouse he holds my lead dog and waits for me to struggle in the knee-deep snow instead of trying to reach me with the dogs in tow.

Under my polar clothes, my DNA remains the same. Despite frequent trips to the polar regions of the earth, my corporeal form believes the president's name is Caesar and that Pompeii is just down the street from the sheep dealer.

I reach Ivan drenched in sweat craving pasta and olive oil.

The blond haired girl stands on her sledge, foot on the brake, waiting for me. I am expecting a snide comment from her. None comes. I am sure she is willing herself to materialize on a different mushing adventure.

Ivan is holding my lead dog's harness in one hand. "I fell," I say to Ivan as I mount my sledge.

"My advice is not to let go of the sledge, no matter what."

"Yes. I see this to be true, now."

He reslings his Winchester and quickly scans the snow covered slopes around us. "Are we okay to go?"

I tell him I am. We get back to the kennel without incident.

Later that evening the blond haired girl says, "You liked that mushing trip, didn't you?"

"Yes, it was fun," I say because there is no upside to any other response.

"Tomorrow there is nothing to do. Maybe we should go again."

"It was an expensive trip and I almost died."

"You didn't almost die."

"But it was expensive."

"I was thinking we only live once and we should go on the longer all day trip to the ice cave."

"Are we suggesting that if I can't be killed cheaply, maybe throwing money at the problem will solve it?"

"Oh come on."

"Seriously. I fell off the sled in the middle of the wilderness. In the dark. It's not going to be light tomorrow or even for the rest of the week and I can't even find my way to the bathroom in our house at night. And did you see? Those dogs just took off. And how good a shot you think Ivan is? You think he could hit a moving bear that came tearing down one of those hills at me while I was flailing in the snow?"

"He stopped your dogs."

"And have you read the brochure for the ice cave trip? It says, 'Not recommended for those who are either claustrophobic or fear entombment.'"

"Oh come on. You're not claustrophobic."

"And I have to pay, like a thousand bucks."

"How many chances will you have to say,'I went mushing in Svalbard and climbed through a glacier cave?'"

"Maybe we should take the Segway tour of Baghdad instead."

She bats her eyelashes and pouts. This is the woman who thought it was fun to be hung by a massive bungee from the open rear door of a C130 circling over the south pole station so she could get digital pictures from a good angle.

Since I can no longer sire young, I must provide adrenaline. This is what the woman wants.

And the next day, I am once again on the dog sled in the Bolterdalen valley in the polar twilight. And then I am on my belly 30 meters below the surface of a moving glacier, sliding through a smooth tunnel in the white ice, six inches high and four feet wide, remembering the guinea pig I had as a child to keep myself from thoughts having to do with being buried alive, the path ahead lit by my LED lamp, my helmet brushing against massive clear icicle stalactites that break and crash against my body inflicting welts and bruises

"I advise not to knock them down," says our guide.

"I agree," I say. "Looks like you could get killed if one of those really big ones hit you."

"Nobody this year," he says.

But it is the beginning of the year.

Signs in the butikken remind us to check our weapons at the door. The grocery aisles are free of carnivorous predators. Here we have subjugated other species: relegated them to cutlets to provide us protein. Here lie the swine, the crab, the hvalbif.

"Hvalbif?" says the blonde haired girl. She hefts the vacuum packed chunk, red purple like a palm-sized blood clot.

The Lonely Planet guide to Scandinavia provides me the English translation, which like most Scandinavian translations is more like a change of accent than a contextual recoding.

I say, "Sound it out," and she stands lip syncing to the word in her head.

"Hvalbif. I don't get it."

"For instance, to the bears we're boybif and girlbif."

The guy at the coffee shop tells us the score. Much easier to get a high powered weapon than rent a vehicle. At least you've paid for the ammo and one way or another they'll get the gun back, is the thinking.

He says, "You should practice shooting, of course, before you leave town. Just to make sure you can work it. People get scared and shoot nothing."

"Where do you practice?"

He raises an eyebrow.

"I mean, can you just shoot anywhere?"

With the look of an amateur trying to decode hieroglyphics he says, "But not toward the people, of course."

"Sure but what if I decide not to take a gun? Wouldn't that just be safer?"

"Why?"

"Because they're dangerous?"

"Well it's okay. Anyway it's your life. We haven't had anyone attacked by bear for at least five years. Except for a woman last week but she wasn't in town. She was over on the hilltop, unarmed. Against strong advisement."

"Which hilltop?"

"That one."

"The one by the church parking lot?"

"Yeh."

"And how badly was she hurt?"

"Well absolutely killed, of course. Did you want anything on this coffee? Perhaps chocolate?"

Longyearbyen is further north than McMurdo station is south. The t-shirts in the duty free shops remind us we are north seventy eight degrees, thirteen minutes. Plow a road and you could be at the pole in a seven hour drive. Twelve by snowmobile, if you can possibly rent one instead of a rifle. The capital of Svalbard doesn't look much different than McMurdo. Sans volcano there are the same mountain ranges, the same sea channels, the same hyper-insulated buildings and dirt roads. But upon slightly closer inspection mighty differences emerge. One difference is you don't have to go to survival school to stay at the SAS Radisson Polar Hotel. Another difference is you take your shoes off when wandering inside. Nobody checks to see if you're cold in Svalbard. There are daycare centers and grammar school yards replete with kids dressed in inches of insulation playing tag under the seething aurora.

The school yards are surrounded by fences. Parents stand outside waiting for the bell to ring and the kids to be released.

"Do these fences keep out the bears?" we ask one of the mothers who has taken an interest in we rare polar winter tourists. Who comes to Svalbard in the 24-hour darkness?

Crazy people asking about polar bears.

"No bears come into town."

"But if they did, do these fences keep them out?"

"But we shoot them first so we don't worry."

We walk down the road to the channel, and then up toward the peaks, toward what appears to be nowhere in polar terms. There is a yellowish blue stain on the horizon through which it's hard to see stars. The glow illuminates the snowy land pierced by stark black mountains draped in ice.

Eventually we come to a sign. It's a triangular pictogram, edged in red, rounded corners, black inside and stamped with a white iconic ursine form.

"So there is an international symbol for 'polar bear,'" I say to the blonde haired girl. "What do you think the words say?"

She doesn't know.

Later we find out it means "True in force all over Svalbard."

The wind bites into our thick clothing and wedges into a gap I hadn't seen when I got dressed. I pull my balaclava up over my nose which I learned in Antarctica was one of the most frostbite-prone areas on the human body.

And unlike Antarctica we have not had to get approval from any agency to walk down this road. And no one has had to make sure we're well-enough equipped. This is Norway where everyone is responsible for himself, and not only is it not the duty of those in charge to see to our safety, but they feel they would be insulting us if they did.

The natives must think we're daft. We're passed by a guy on a snowmobile, who must not be Norwegian because he slows and points to the sling on his shoulder, then takes off at speed. The dark metal melts into the night and it isn't until his red taillight fades to a point that I realize what he means.

"I would have gone for the Winchester," I say. "We should have shot at some of that driftwood for practice."

"But they were closed," she says. "And I'm not sitting around all weekend waiting for them to open. How often do you find yourself on Spitzbergen that you want to sit around a hotel room?"

"Aren't you interested to see what's on TV in Svalbard?"

She doesn't dignify the question. So I say, "Well, anyway, I probably wouldn't even see a polar bear in this gloom until it was too late. Damned isbjorn could drop down from one of these hills in a few seconds. We'd probably wind up shooting each other."

We walk until we realize the only reason we're not shivering is because we're walking. Then we head back toward the man-made yellow glow.

And on the high-cost tourist treks the guides do not insult you by making sure you have prepared appropriately for your adventure experience. If you are not dressed well, you will freeze. If you have not eaten you will starve. If you are thirsty you will dessicate. Proficiency is presumed. Incompetence is a surprise and upon encountering it they will do their best to keep the polar-challenged from dying, but this will detract from the experience of the others on the trek.

So when one on our dog sledding party discovered she was plunging into hypothermia half way through our trip toward the glacier, the guide simply pulled off one of his clothing layers and gave it to her.

"But now he's missing a coat," I said to the blond haired girl.

"He must be used to it."

"But it's minus twenty."

"But he gave her his coat. He must know."

"Do you think he'll freeze? He's got the gun."

"Maybe you don't freeze if you're from here."

"All human flesh freezes at the same temperature."

"What do you want me to say?"

"These Norwegians are very hearty people."

"They are hearty."

And when the brochure says: "You will have the experience of dog sledding, from choosing your dog to mushing across the tundras," they mean that you should be ready to go to the kennel and take the animal from its house and lash it to the harness.

Have you never been dog sledding? Then you will learn how this is done. You will learn how not to be bitten, which is to stay away from the mouth.

Our guide is Ivan. He says, "The first 400 meters out of the kennel are the hardest. There is a steep drop and a turn to the left. There is the feeling of falling off your sledge so do not fall off."

"What happens if I fall off?" I ask Ivan. I was born one to fall off things. It took me twenty years to learn to ski. I am certain I will not become a musher in my first 400 meters.

"You will then try not to fall off. This is the strong advisement. Please do not fall off. It is very difficult because once the dogs sense there is no person controlling them, they show the tendency to run very fast away from everyone. And of course it is night and there are bears."

"But if I fall off you can get the dogs back, right?"

"With some difficulty, this can be done. But I advise you to not fall off and it will be okay. And if you fall off you will not let go of the sledge no matter what. Please- no letting go." The LED lamp on his head needs no adjustment but he moves it anyway, and in doing so causes my unconscious headlamp check. My light is pointing toward the constellation of Orion and not toward anything that needs to be visible to an amateur musher. This I fix.

I mount the sledge the way I have been shown - one foot on the runner, one on the brake. I'm wearing mittens over my glove liners, so gripping the sledge handle requires more force than I expect.

The dogs howl and yap the way my neighbor's dog did before it died of heartworm. The dogs who have been left at their little dog houses in the snow join in the chorus. Ivan says, "They know what is going on and that they are not picked."

"Poor doggies," I say, suggesting I should have more than six of them lashed to my sledge. These are little guys compared to the 120-pound Akita I have at home. They don't weigh more than 30 pounds each and look emaciated. I wonder how they could pull a que ball across a billiard table. Ivan says, "Don't worry, it's enough," and his sledge begins to move. When my dogs see the lead sledge take off, they lunge forward against their harnesses and even with all my weight on the snow brake the contraption lurches.

I ease up on the brake and we begin to move smoothly out of the kennel gate and toward the open expanse of arctic twilight beyond, but immediately my lead dog disappears over what I discover to be a small cliff. With pressure on the brake I head over behind them, worrying all the time that with my mass combined with that of the sledge I outweigh the small dogs by over two times, and if I gather momentum I will pass them and this is not a cartoon and dragging the dogs downhill will be some degree of inadvisable badness I am unwilling to withstand. So I am hard on the brake and apologizing to those tiny creatures who are pulling so hard -

"I'm sorry doggies. You don't have to pull so hard because I have the brake on."

God has blessed the simple creatures with the lack of a cerebral cortex, so they have no means to become resentful and follow only their instinct, which is to pull until they die.

The trail curves hard left while we are descending. On the off camber turn my uphill runner tips and loses contact with the snow.

I shift my weight and concentrate on not falling.

And I do not fall.

Later, however, when I am not concentrating I do fall but I do not let go of the sledge and manage to drag myself back onto the moving runners like a hobo mounting an empty train car.

And even later, on the way back I fall off the sledge and lose my grip on a steep downward slope. As I roll to a stop I see my dogs accelerating forward, enjoying the sudden lack of an extra hundred kilos.

So I start screaming because I remember the woman who was absolutely killed for not following the advice, and I'm trying to move forward in the fading twilight, in a polar valley thousands of miles from my warm California home, surrounded by polar bears who haven't eaten in weeks -- aye, the females hibernate but the males hunt all winter -- unarmed in snow up to my knees, unclear which direction is the right one except to follow the sled tracks in the never ending darkness, night blind since laser surgery, frigid Svalbardian air seeping through the gap between my wind pants and parka, having forgotten nearly all of my Antarctic survival training (does it even work in the arctic?) --

this is an appropriate way for me to die, I suspect. If they had asked me before birth: "How do you want to go out?"

"What are my choices?"

"Well, there's cancer. Heart attack. Dementia, maybe accidentally eat rat poison. Violent crime. Air crash. Losing your dog sled in the Bolterdalen valley and freezing/being eaten by polar bears. Auto accident. That kind of thing."

"Are there other choices?"

"Many."

"I kind of like the dog sledding idea. It's unique."

"Very creative. Shall we put you down?"

"Please."

But I do not die in the Bolterdalen valley.

Instead, Ivan stops my dog sled somewhere far from where I have come to rest on the hillside. And because he is Norwegian and this is not a vacation for sissies who want to see Mickey Mouse he holds my lead dog and waits for me to struggle in the knee-deep snow instead of trying to reach me with the dogs in tow.

Under my polar clothes, my DNA remains the same. Despite frequent trips to the polar regions of the earth, my corporeal form believes the president's name is Caesar and that Pompeii is just down the street from the sheep dealer.

I reach Ivan drenched in sweat craving pasta and olive oil.

The blond haired girl stands on her sledge, foot on the brake, waiting for me. I am expecting a snide comment from her. None comes. I am sure she is willing herself to materialize on a different mushing adventure.

Ivan is holding my lead dog's harness in one hand. "I fell," I say to Ivan as I mount my sledge.

"My advice is not to let go of the sledge, no matter what."

"Yes. I see this to be true, now."

He reslings his Winchester and quickly scans the snow covered slopes around us. "Are we okay to go?"

I tell him I am. We get back to the kennel without incident.

Later that evening the blond haired girl says, "You liked that mushing trip, didn't you?"

"Yes, it was fun," I say because there is no upside to any other response.

"Tomorrow there is nothing to do. Maybe we should go again."

"It was an expensive trip and I almost died."

"You didn't almost die."

"But it was expensive."

"I was thinking we only live once and we should go on the longer all day trip to the ice cave."

"Are we suggesting that if I can't be killed cheaply, maybe throwing money at the problem will solve it?"

"Oh come on."

"Seriously. I fell off the sled in the middle of the wilderness. In the dark. It's not going to be light tomorrow or even for the rest of the week and I can't even find my way to the bathroom in our house at night. And did you see? Those dogs just took off. And how good a shot you think Ivan is? You think he could hit a moving bear that came tearing down one of those hills at me while I was flailing in the snow?"

"He stopped your dogs."

"And have you read the brochure for the ice cave trip? It says, 'Not recommended for those who are either claustrophobic or fear entombment.'"

"Oh come on. You're not claustrophobic."

"And I have to pay, like a thousand bucks."

"How many chances will you have to say,'I went mushing in Svalbard and climbed through a glacier cave?'"

"Maybe we should take the Segway tour of Baghdad instead."

She bats her eyelashes and pouts. This is the woman who thought it was fun to be hung by a massive bungee from the open rear door of a C130 circling over the south pole station so she could get digital pictures from a good angle.

Since I can no longer sire young, I must provide adrenaline. This is what the woman wants.

And the next day, I am once again on the dog sled in the Bolterdalen valley in the polar twilight. And then I am on my belly 30 meters below the surface of a moving glacier, sliding through a smooth tunnel in the white ice, six inches high and four feet wide, remembering the guinea pig I had as a child to keep myself from thoughts having to do with being buried alive, the path ahead lit by my LED lamp, my helmet brushing against massive clear icicle stalactites that break and crash against my body inflicting welts and bruises

"I advise not to knock them down," says our guide.

"I agree," I say. "Looks like you could get killed if one of those really big ones hit you."

"Nobody this year," he says.

But it is the beginning of the year.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home