Grand Canyon

"You still do," I said. "And when I was a kid I rode my bike to that hardware store for nails to build forts. I remember we built a two story deal out of scraps in the back wood where they tossed all the construction cast offs."

"Two stories? You were lucky you didn't kill yourselves."

"Not only for that," I said.

From the padded plastic car seat in the back my 2-year old daughter said, "When I was a lion I used to eat birds and mice."

"Were they tasty?" I said. A quick glance in the rear view mirror. She was straining to see past the sides of the car seat and out the side window. A small group of crows ascended from the bank's front lawn.

"But I don't eat them now," she said.

"How about mice?"

"But maybe I can have a mouse."

"For dinner?"

"No, silly. To live in the mouse house."

My wife said, "When I was a tiger I used to eat chickens."

Tiny mental wheels calculated. The child said, "Mommy, you not a tiger. You're mommy."

I said, "Daddy's a lion."

"No, Daddy. You a bird."

"But don't the lions eat the birds?"

"But you don't need scared, Daddy. Yesterday I a lion. Today I Michelle."

And then twenty two years went by.

Last week I stood with my toes on the edge of the Bright Angel limestone, looking down past the Redwall to the Vishnu Schist. From the south rim tourist area there's only one place you can get a glimpse of the mighty Colorado that carved the Grand Canyon and I was not at that place. But if I could get some height, fly out over the abyss, perhaps then I could see it.

"I first saw this twenty five years ago," I said, trying to remember how it felt to fall through miles of open air and then catch myself as if my toes touched the rug at my bedside.

"What?"

"It was like I'd never been born. I felt so small."

The blond haired girl joined me at the edge of the precipice.

She said, "And then what?"

I thought about flying. Adding the gyrations of up and down to my usual two dimensional motation, and how this version me of doesn't well tolerate amusement park spins and drops. When I was younger, I craved it.

"Am I remembering a dream?"

"Are you?"

"I'd lived in the suburbs of big cities my whole life. So many different places that are all the same. The farthest you can see at any one time was either to the next stop light or upward to the moon. When I got here, I thought I'd reached heaven. It's an epiphany in rock. One of those indescribable visions you have in a dream that dissolves to nothing when you turn on the bedroom light. I remember standing here thinking angels were speaking to me. I think they are."

She searched me with her eyes and I wondered if my emotions were visible. Maybe she could decode them. Explain them to me the way a doctor tells you which pains are benign, and which require chemotherapy.

But she said, "Ok. So you saw the great outdoors for the first time and it opened your eyes to something new."

"Maybe that's all it was." A lump of something firm and sad rose in my throat and I swallowed it down. Keep it down.

"What's wrong?"

In my mind I repeated, "It was something else," but none of the words made it to my lips.

Instead, my eyes welled with tears and I took her hand and led her from the brink of the most beautiful descent on earth, back to the rental car.

The canyon is different every second of every day. As the hour hand arcs, sunlight swings through crevasses and over wide plains simultaneously revealing what had been in shadow and hiding what had been baked under the oppressive heat of full day. Rocks turn from golden, to orange, to red, to brown.

Distances are deceptive. A small head-sized chunk of granite a few feet away turns out to be a house-sized boulder a mile distant. The green thread of river seen from the rim becomes a seething monster at the shore, replete with man eating standing waves and rapids that pulverize human contrivances with an ease that borders on thermonuclear. This is the water that ate through the earth. This is the power of Shiva, there to remind you that the dispassionate destruction of solid rock yields a silent gargantuan beauty.

Every death is a birth.

Twenty two years ago I hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon with a few other engineer friends from RCA in New Jersey. We took the South Kaibab trail to the Phantom Ranch. It's a steeper yet shorter route than the Bright Angel. As the trailhead is not close to the tourist centers, it's less traveled. Though unlike the Bright Angel trail where running water is available every 1.5 miles, there is no available water on the Kaibab. So one must carry his own - enough to assure safe arrival at the bottom. This quantity amounts to about a gallon for the downward journey, provided one leaves before daybreak and walks in the colder part of the day.

We took our trip on July 4th weekend. Temperatures at the rim were in the 90's Fahrenheit, and at the bottom they would be closer to 120F.

I had been anticipating the trip for the year it took to plan. After my first look at the canyon some two years prior I had been yearning to get back the way Roy Neery needed to meet the aliens at devil's tower. I dreamed of the canyon. I read books. I reviewed the photos I had taken over and over.

And then I was there at the banks of the Colorado at the Phantom Ranch. It was 118F in the shade.

That didn't stop me from filling up my canteens and walking up the North Kaibab trail so I could say to myself I'd been closer to the North Rim than anyone else on our trek.

I remember sleeping fitfully in a bunkhouse with 7 other hikers. Being roused at 4AM by the rangers, fed a pancake breakfast at 5, and being shooed off on our way back up to the south rim before the July temperatures turned us into a death statistic in the Park's Department register.

My friend Mel and I made it from the Phantom Ranch to the south rim tourist centers by 10AM. We were young and full of energy. We pulled away from the rest of our team early on, and walked most of the journey with only each other as company.

The whole time I was certain there was someone walking with us. I could hear footsteps behind me.

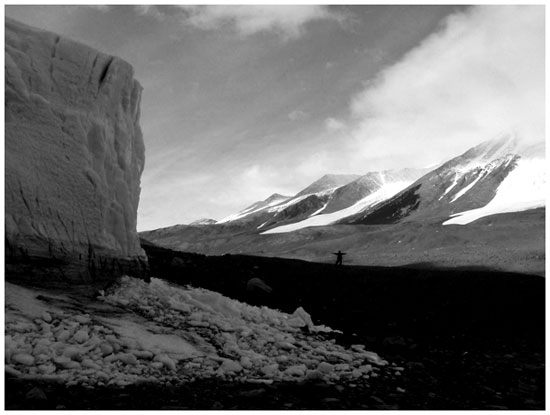

Later in life I read the story of Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance, and how when crossing South Georgia island he felt there was a fourth member of the team hiking along side them.

With perfect historical hindsight we can develop the explanation that by the time Shackleton and his men reached South Georgia he was starved, sleep deprived, dehydrated, and probably close to death, and that in that state a man can hardly be blamed for hallucination.

But I was none of those things.

And I am not now. And the companion is with me, next to me as I write.

We are born and we die many times in one life. Each death teases us, lures us into the complacency of stasis. It's far easier just simply not to try than to endure the trials. Each death suggests silence. Calm. Remain and all is well.

Each birth, an elevator door opening on a room we've never seen, home nowhere in sight.

At each juncture, the opportunity to speak.

At each of those times the angels pause, listening, awaiting our guidance. They can't live down here. They can't even breathe. They watch us they way we absorb television pixels.

-What made you decide?

-What will you do next?

-We can't believe you got this far. Look at what happened.

-How does it feel?

The Grand Canyon is sacred ground to the Yavapai, Havasupai, and the Hopi.

Far from the tourist trails there is a cave. In the cave is a Kiva. At the center of the Kiva is the Sipapu, a hole in the ground that descends beyond the center of the world to the beginning of all creation. It is the channel life took to Earth's surface. It is the origin of all of us, all time, all things.

I know it is here. Standing on the white shale at the rim it vibrates the stones under my feet and sends a pure note through on the wind. The camera laden tourists push past and every now and then one will pause and ask another, "What was that? Did you hear that?"

I was like that, once.

"Are you okay?" said the blonde haired girl.

And I could hear her the way someone lost hears the the rescuer's calls echo off the stone.

It's been a lifetime since my last descent of the Grand Canyon. My lifetime. Now in climbing it steals my breath. It tears at my heart and legs. The thought crossed my mind on the ascent once, maybe twice - I won't make it.

Now at the rim after seven hours climb she asks, "Are you okay? What's wrong?"

The Canyon is immutable. Though it changes constantly, I would recognize its brink through the darkest night and deepest snows. But I am no longer the young man who ascended from the Ranch in five hours. That one is dead and this scarred and imperfect replica has risen in his place.

I can put my feet in the same places I did those years ago and stare out over the gulf to the shattered rock knowing that the Canyon is measured in millions of lifetimes since the first being emerged from its depths. But likely, only one lifetime from now I shall not stand again in this holy place.

"What's hurting?"

And because we live poetic lives, an osprey swooped down from behind us and soared into the abyss. We watched as it became a silhouette became a dot became nothing against Shiva's temple.

I said, "When I was a bird I killed small animals and taunted the lions."

But no one needs fear me now.

Today I am just a man.