Bella Luna

I have seen a moon rocket. With my own eyes.

I have been in the presence of the massive machine. Five F1 engines capable of administering the thunderclap of Zeus upon which men would be propelled toward the holiest grail of the earthbound dreamer. It was a skyscraper painted white and black in a mosaic of roll patterns. Adorned in lettering that informed everyone the United States owned that beast. Designed it. Flew it.

Stand within three miles when it was launched and it would thump the breath from your lungs.

In 1972 my dad drove mom and the four of us kids down to Florida from Chicago on family vacation, with the objective of visiting a new theme park Disney had put up in a swamp outside Orlando. And in those days Disney was afraid of spinning its guests too violently. The so-called "rides" were placid excursions past well-painted dioramas in the adult equivalent of a pram. I enjoyed it about as much as I did wearing a starched white shirt while sitting in a pew at church for an hour on a stifling hot Sunday morning. No doubt most of my disgust at the milquetoast brand of entertainment dealt out by the Magic Kingdom was driven by my nuclear obsession. By the knowledge that in all my thirteen years of life I had never been closer, and might never again be within spitting distance of it.

Fifty miles east of Mickey Mouse we were sending men into space. There were computers and trajectories. Calculations and orbits. Weightlessness and a sky so black if you looked between the stars you could see the inside of God's mind.

I was obsessed with the space program. I loved everything about it. I knew all the astronaut's names and backgrounds. To this day I can't hear the name James Lovell without immediately thinking of Frank Bormann. Together on Gemini. Together that Christmas eve in 1968, looping around the moon, reading from the Book of Genesis, first men to see the dark side of the moon. They will always be Bormann - and - Lovell to me. (And then I think of poor Anders, who's name doesn't map with the same syllabic beat.)

I knew the stats on the rockets. I watched every second of news coverage I could get to when I wasn't in school. I grew familiar with the newscasters covering the space flights and their idiosyncracies. Jules Bergman on ABC. Walter Cronkite on CBS. John Hart and Roy Neal on NBC.

Even though they couldn't appreciate it the same way I did, on the eve of my thirteenth birthday my parents dragged my younger siblings over those fifty miles, away from Mickey and Goofy, toward the coast where America was launching rockets.

I remember that trip. How the cumulus clouds loomed like floating aircraft carriers over the flat yellow-white Floridian soil. How the brilliant sun pressed down on my shoulders like a thick mat of warmth. Miles of scrub and occasional palm trees until we reached the shore where the contrast between the white sand beach and the blue-black ocean drew a line that split everything into earth and sky.

And there on that line was the tremendous cubic VAB, visible for miles, hovering on the horizon in the distance and seeming to follow along with you as you drove the way the moon does when you come home late at night from Grandma's. The Vehicle Assembly Building, so huge if they didn't circulate the air fast enough it would rain inside. The Vehicle Assembly Building, so massive that when you're close enough to see it in full, the cars parked at its base are mere pixel-sized dots in your visual field.

The VAB in which Saturn Vs were put together. The twentieth-century's answer to the pyramid. Spaceport U.S.A. Gateway to the stars.

I remember my brother yelling at me, in those days before automobile seat belts, when in my zeal to keep my eyes on that human artifact I climbed over him on the seat. I remember walking into the visitor's center, past the reclining rockets of the past. The Mercury Redstone. The Titan. The Atlas. There's the launch umbilical tower, bright porous red, a massive steel monument to human achievement. We will own the sky someday, we will.

My father at the cashier -- do you want the 1-hour, the 2-hour, or the 3-hour tour?

Three. It must be three. And my mother rolling her eyes, trying to figure out how she's going to pacify my three siblings for whom this trip is torture to be endured before returning to the Dumbo ride.

The Dumbo ride. Spinning in a fiberglass baby pram, versus crossing hallowed ground. John Glenn has stepped here. Neil Armstrong. Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, and Ed White died right there, the only Americans to have died in the space program and it happened on the ground during a test.

High pressure oxygen. The door that opened inward. Do you want to know more, Dad? Gus Grissom of Liberty Bell 7. Ed White, the first space walk. Roger Chaffee -- to be his first flight. Mom, that thing on top is not an antenna, it's the escape tower rockets. It pulls the command module off in case the Saturn V is in danger of exploding.

The difference between a missile and a rocket is that a missile is unmanned.

The size of the American flag painted on the S-IC stage is the same size as this bus. That thing that looks like a launch pad on tank tracks is the crawler. They put the rocket on it and they drive it to the pad.

We are a mile away from the most powerful vehicle ever constructed by mankind. On launch day, we couldn't get within three. And the astronauts are going to be on the pad soon for a dry run. When they are in the command module, we can't get this close, either. They may have to eject.

Those engines are twice the height of a man. Millions of pounds of thrust. Engines built by Rocketdyne. The LEM by Grumann. The S-IV-B by Rockwell. That's the third stage. One engine.

You want to know what I want to do when I grow up? This is what I want to do when I grow up. I want to build these. I want to ride in these. I don't know why I love it so much but I do. Can I have your camera? Can I take pictures of this? I know it's just a piece of concrete. It's the launch bunker for the Redstone.

It is the eve of my thirteenth birthday, the Saturday before Easter, Apollo 17 stands at the tower, waiting to be fueled. The last moon rocket. It will be sent up at night a few days from now and I will be back at home. Can we stay for the launch? Is there any way?

I bask in the energy of the presence of the greatest technical achievement that has ever been in the history of human engineering. They built pyramids and Sphynxes and one-hundred ten story office buildings. Hanging gardens in Babylon and the Hoover Dam. But now we are going to the moon. The universe is wide open for exploration. Today the moon, tomorrow, Mars. My grandchildren will be born at a base in Clavius crater. Pan Am is taking orders for the first ticket to the moon, and they will get there just like we saw in that movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, I know they will.

When I was thirteen I felt passion for the first time in my life. Now I knew what it meant to be ecstasy -- to be outside of myself with such focus that I was not conscious of my own safety. From that day forward, I would become an engineer. I would become an explorer of worlds and a conqueror of the mystical religion of technology.

For years I had the pictures from that trip in a Scrapbook I kept under my bed. When I moved away from home in 1977 and I abandoned everything that made me a kid the scrapbook with my picture of the Saturn V disappeared. My mom probably trashed it.

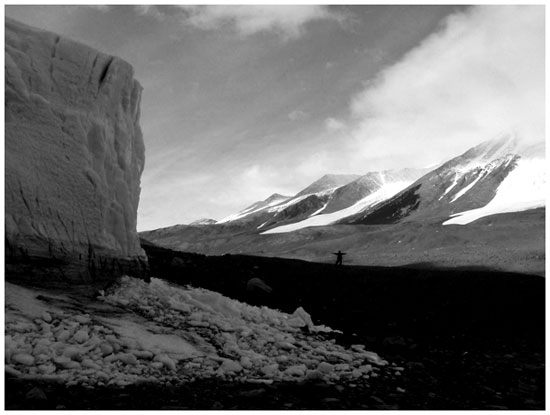

I eventually did become an electrical engineer. It was clear from the time I was seven that I'd never become an astronaut with myopia as bad as mine. And besides, I'm too tall to fit in an Apollo-era space capsule. But I did go to Antarctica, which was my Sea of Tranquillity. I can look at myself in the mirror and say without hesitation, I never lost that passion I had as a kid, and given the chance, despite any risk, I would go to the moon.

Yes I would.

*

On the eve of my forty-sixth birthday, I saw Neil Armstrong. He gave a lecture at our local community college.

Now, thirty six years after his moon walk, he's seventy-four years old. He wears glasses as thick as the ones I wore when I watched him on television as a thirteen year-old. He stutters. He still gets choked up when he talks about standing on the surface of the moon, looking at twenty-three degrees above the horizon and seeing the blue-blue earth hanging in the infinite blackness that is our universe. He leaves no doubt that flubbing man's first words on the moon were a result of his speech patterns, and that if he were to do it again, he'd gladly make the same mistake. "It's just so Neil," would be the way one who knew him would say it. It humanizes the grandeur of the achievement. As it should. Because all our achievement is human.

On the eve of my forty-sixth birthday, I was in the same room as my hero. He's a very affable human being. He's doing his best to remain a simple man. Handles the public spotlight in his down-home, midwestern way. Does speaking engagements to pay the bills.

He's got to be careful about what he says. He can't be overly critical of anything, lest one organization or another seek to use his persona to further their cause. He makes jokes about politicians. He's an environmentalist without being a tree hugger. He's a conservative without the religion.

He avoids answering questions he doesn't want to address in the same manner as a skilled politician. By now he's done so many press conferences and state visits, handling the press is encoded in his DNA. Yes, he flew the LEM to within some few seconds of engine burnout. Yes, Buzz Aldrin took the Catholic sacrement of Holy Communion on the lunar surface. Yes, some people think they see UFOs, and there are strange things out there but they're probably not evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Yes, flying the X-15 to 4000 miles-per-hour was a rush.

The goal of going to Mars is probably attainable, but is more of a pipe-dream than an actual program. Why not go back to the moon, which remains almost entirely unexplored, with an order of magnitude less effort?

In the 1960s, he flew a Gemini space ship around the earth, did mankind's first-ever docking in space, and successfully landed in the ocean to within eye-shot of the carrier, all with the aid of an analog computer whose memory capacity was 2k and whose interface was a single yellow light and a 7 digit display. Imagine what could be done today, he says without saying.

He talks about the dangers of space--the risks that were taken. A single solar flare would have killed them all, subjecting them to five times the lethal dose of ionizing radiation in an hour -- and they were lucky that in all the Apollo missions there was never a solar flare during the flight, even though the sun was at a sunspot maximum during that period. That problem should be addressed before we think about spending two years in transit to and from Mars.

Yes, he has spoken to every man who went to the moon, and the 12 that walked on its surface, and yes, every one internalized the experience and emerged with a heightened sense of spirituality. They all feel more concerned about the fate of the environment as a result. All feel closer to the creator. But Neil is not a man who has ever worn his heart on his sleeve, so he leaves it at that.

Seventy-four years old. Thick glasses and a stutter. He thanks us for our time -- says it's the greatest gift one person can give another -- both at the beginning and end of his talk.

Here is the first human being to set foot on a celestial body other than the earth. Astronaut. Pilot. Explorer.

My kids sort of understand what he means to me, but mostly they don't. I can say that he is one of my heros and I feel like I'm a kid again when they run the reel on the moon landing. "One small step..." the compressed voice comes through the thirty six years, the grainy black-and-white picture we've seen over and over.

And there he is right in front of me. Bowing and smiling. Perhaps it's hard for the people who love me to understand that I would not be me without him.

*

What do kids do these days? Who are their heroes? When they dream of reaching the unattainable heights, where do their minds go?

When I was thirteen I stood on the front lawn of my home in the Chicago suburbs and looked up at the moon in the late afternoon sky and I knew there were men on it at that very moment. Men had traveled in a rocket I had seen, and were traversing the lunar surface, collecting rocks, looking back toward the earth while I looked upward at them.

That doesn't happen anymore and I think there is less hope in the world because of it.

People should have childhoods. Nowadays we expect kids to be adults from the time they can select a channel on the satellite TV. We subject them to "adult situations" as the TV/Movie raiting system calls it. We prosecute them in our courts as if they've the benefit of decades of world experience. We push them to achieve from the time they're born. Here in silicon valley, parents brag about ten-month olds who utter sounds that seem like words. There are two-year olds who recognize printed text. There are three year olds who can tell you the difference between a symphony and a fugue.

Yet we score lower on tests than those of other countries. We're less literate, less capable around numbers.

I had an actual childhood. I was treated like a child, to my chagrin, and the only responsibility I was afforded by my parents was to keep my grades up and keep my siblings from burning down the house when my parents went out with their friends on the occasional weekend evening.

When I was a kid, we were sending men into space and we knew we'd have colonies on Mars someday. We could go as far as we wanted. I knew that was true and to be part of it I would have to excel in my studies and distinguish myself as a student.

Because I knew that all astronauts are smart. They had a mastery of math and the sciences. They were in tip-top physical condition. They served their country and their families. An astronaut was brave. An astronaut was virtuous. You could trust an astronaut with your life savings or your best girlfriend.

When I was a kid that's what a lot of us wanted to be. Virtuous. Brave. A man who lived in service of God and country, and who explored the far reaches of the universe. Someone who designed and worked with machines that could bring you to the brink of incredible terror -- the terror of distant nature, so huge and uncaring that the fear it inspired became awe, became love.

We are all born explorers and whether he likes it or not, every kid has all of life to cross into. From the nothing before birth, a kid has to learn everything adults take for granted. It's the nature of a young person to seek and learn.

If I was young today, what would I hang onto to give me an explorer's hope? What would take my breath away the way Apollo 17 did? Who would I most want to emulate in life?

Even though I know there would be something to replace my desire to become a lunar astronaut, I don't know what it could possibly be.

*

Over the past three months I built a model of Apollo 17. It's five feet tall. It's meant to be flown, so it has a place for a big "G"-class model rocket motor. It has kevlar parachutes.

I got the kit from Apogee Components, which is a one-person company in Colorado. Two-hundred dollars worth of cardboard tubing and paper diagrams came. Three months later I finished it. Though it could have been painted like any of the 10 Saturn Vs, the decals on mine are arranged in the exact configuration of Apollo 17, the very last moon rocket, the one I saw when I was thirteen.

I probably will never fly it. I don't want it broken.

It didn't really fit anywhere in my home, so I brought it to the office. And immediately, my colleagues came into my office to look at it. Most of them are my age. All of them are engineers. The same thing happened to all of them.

They stared at the model and got one version of misty-eyed or another. They each said, "I became an engineer because of this," and, "how come we don't do things like this anymore?" and "I remember when I saw Apollo 15 and the lunar rover," and, "Did you know they had eye charts in the early Mercury space craft because they didn't know if their eyeballs would pop out in the low pressure atmosphere?"

"How long did it take you to build?" one asked me.

"Three months," I said.

And I expected him to ask, "Why?" but he never did. Not one person asked me why I would spend three months of my spare time sanding and painting cardboard tubes to create a 1/70th replica of the moon rocket.

Because it is our first true love. Guys my age learned about falling in love following the space program. We all fell in love first with rockets and space, and later with our spouses.

Thirty six years ago, each of us was going to be a part of it. We read Boy's Life and built plastic models from Revell and Monogram in preparation for the real thing -- and knew without doubt that someday there would be a real thing.

Because when I was a kid, it was possible for an engineer to do anything.

*

Today, on the eve of my birthday, I think about the space program. I have seen an Apollo moon rocket and now Neil Armstrong. I was extremely fortunate to have been born when I was. I was never drafted and taken away to Vietnam. I saw the fall of the Berlin wall. I participated in the explosion of the semiconductor industry, and worked at Intel at the time when microprocessors became a ubiquitious appliance.

I was thinking about the stars. Watching Apollo 11 lifting off the pad with Neil Armstrong himself standing under the screen, Neil and Buzz and Mike floating in space, the first steps on the moon, it reminded me of the big hole we left in the lives of lots of young people by not doing the things that inspired some of us. Yes there were critics. For every mission, there are hundreds who will extol the virtues of staying at home, fixing things here, and things always need fixing. Always. There's no lack of reasons to not do something. Expense. Time. Focus.

Let me say to you, these critics will for now and always remain outside the effort of human advancement. They're there to test you. You will never achieve any of your potential listening to people who advise you to avoid the risks and play it safe and to not waste money with your head in the clouds when there's plenty of work right here at home.

Bullfuckingshit.

It takes a kid to decide a person should go into space, an adult would never do it. Too impractical -- because there's nothing in particular out there. But kids know there's everything in particular there. It takes a kid to decide we should walk on the moon, not because it has a fiscal, religious, social, or political purpose, but just because it's the plain ordinary fucking coolest thing a person could ever do, and the very idea of it is gold to the rest of us. The very idea of it makes us what we are.

I think we're lacking as a nation. I think the lack of a government-sponsored exploration program -- to explore ANYTHING -- makes us berift as a people. We have a gigantic hole where our imaginations should be and we've filled it with the soil of human nature that takes the place of anything we fail to do. We've filled our lack of exploration with fear. We're becoming a society of fear. Fear of terrorism. Fear of disease. Fear of lack of oil. Fear of despots. Fear of traffic accidents. Fear of financial ruin. We are afraid of everything and it's getting worse. Like a cornered animal we're showing our teeth ever more frequently, forgetting the moral obligation we have as the strongest to withdraw from arms. My dad used to tell me I would face his wrath if he caught me striking a girl or a little kid, even when one hit me first, because as the stronger party, I had the obligation to take the punishment and walk away. Revenge is the haven of the weak of spirit, the unimaginative, and the enemies of hope.

Because we no longer explore and face the dangers nature has to offer, we have nothing better to do than to culture our fear of each other, and use our technical might in the pursuit of the destruction of an ever growing list of enemies. And the list grows as our fear grows, and as our fear grows our pain grows, and we find others upon which to exact our revenge.

We need a space program. We need exploration. We need to be able to follow the reality-TV event of the year when man sets down on the moon again. When someone walks across the red plains of Mars. We need human exploration because without it, we are simply ants in a colony, aimless pursuing further existence without the potential to BECOME.

I nearly burst into tears watching the men in Houston leap for joy when they heard the words, "Houston: Tranquility Base, here," because it was an achievement of such grandeur and innocence. The motivation for the space program was all about beating the Communists -- but had absolutely nothing to do with it in the end. In the end it was a couple of guys on the moon, eating communion and flubbing their lines. Short guys who fit in space capsules. Human achievement, despite the cold war.

Something a kid could grab onto and hold for his whole life.

Last night with my own ears I heard Neil Armstrong flub another line -- he said: "Someday I believe we will send unarmed men to Mars. I mean, manned and unarmed vehicles. Well, always unarmed."

But I knew it wasn't a misstep, because he didn't screw up a single sentence the rest of the evening.

I guess if you knew him, you'd have said, "That was so Neil."

I have been in the presence of the massive machine. Five F1 engines capable of administering the thunderclap of Zeus upon which men would be propelled toward the holiest grail of the earthbound dreamer. It was a skyscraper painted white and black in a mosaic of roll patterns. Adorned in lettering that informed everyone the United States owned that beast. Designed it. Flew it.

Stand within three miles when it was launched and it would thump the breath from your lungs.

In 1972 my dad drove mom and the four of us kids down to Florida from Chicago on family vacation, with the objective of visiting a new theme park Disney had put up in a swamp outside Orlando. And in those days Disney was afraid of spinning its guests too violently. The so-called "rides" were placid excursions past well-painted dioramas in the adult equivalent of a pram. I enjoyed it about as much as I did wearing a starched white shirt while sitting in a pew at church for an hour on a stifling hot Sunday morning. No doubt most of my disgust at the milquetoast brand of entertainment dealt out by the Magic Kingdom was driven by my nuclear obsession. By the knowledge that in all my thirteen years of life I had never been closer, and might never again be within spitting distance of it.

Fifty miles east of Mickey Mouse we were sending men into space. There were computers and trajectories. Calculations and orbits. Weightlessness and a sky so black if you looked between the stars you could see the inside of God's mind.

I was obsessed with the space program. I loved everything about it. I knew all the astronaut's names and backgrounds. To this day I can't hear the name James Lovell without immediately thinking of Frank Bormann. Together on Gemini. Together that Christmas eve in 1968, looping around the moon, reading from the Book of Genesis, first men to see the dark side of the moon. They will always be Bormann - and - Lovell to me. (And then I think of poor Anders, who's name doesn't map with the same syllabic beat.)

I knew the stats on the rockets. I watched every second of news coverage I could get to when I wasn't in school. I grew familiar with the newscasters covering the space flights and their idiosyncracies. Jules Bergman on ABC. Walter Cronkite on CBS. John Hart and Roy Neal on NBC.

Even though they couldn't appreciate it the same way I did, on the eve of my thirteenth birthday my parents dragged my younger siblings over those fifty miles, away from Mickey and Goofy, toward the coast where America was launching rockets.

I remember that trip. How the cumulus clouds loomed like floating aircraft carriers over the flat yellow-white Floridian soil. How the brilliant sun pressed down on my shoulders like a thick mat of warmth. Miles of scrub and occasional palm trees until we reached the shore where the contrast between the white sand beach and the blue-black ocean drew a line that split everything into earth and sky.

And there on that line was the tremendous cubic VAB, visible for miles, hovering on the horizon in the distance and seeming to follow along with you as you drove the way the moon does when you come home late at night from Grandma's. The Vehicle Assembly Building, so huge if they didn't circulate the air fast enough it would rain inside. The Vehicle Assembly Building, so massive that when you're close enough to see it in full, the cars parked at its base are mere pixel-sized dots in your visual field.

The VAB in which Saturn Vs were put together. The twentieth-century's answer to the pyramid. Spaceport U.S.A. Gateway to the stars.

I remember my brother yelling at me, in those days before automobile seat belts, when in my zeal to keep my eyes on that human artifact I climbed over him on the seat. I remember walking into the visitor's center, past the reclining rockets of the past. The Mercury Redstone. The Titan. The Atlas. There's the launch umbilical tower, bright porous red, a massive steel monument to human achievement. We will own the sky someday, we will.

My father at the cashier -- do you want the 1-hour, the 2-hour, or the 3-hour tour?

Three. It must be three. And my mother rolling her eyes, trying to figure out how she's going to pacify my three siblings for whom this trip is torture to be endured before returning to the Dumbo ride.

The Dumbo ride. Spinning in a fiberglass baby pram, versus crossing hallowed ground. John Glenn has stepped here. Neil Armstrong. Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, and Ed White died right there, the only Americans to have died in the space program and it happened on the ground during a test.

High pressure oxygen. The door that opened inward. Do you want to know more, Dad? Gus Grissom of Liberty Bell 7. Ed White, the first space walk. Roger Chaffee -- to be his first flight. Mom, that thing on top is not an antenna, it's the escape tower rockets. It pulls the command module off in case the Saturn V is in danger of exploding.

The difference between a missile and a rocket is that a missile is unmanned.

The size of the American flag painted on the S-IC stage is the same size as this bus. That thing that looks like a launch pad on tank tracks is the crawler. They put the rocket on it and they drive it to the pad.

We are a mile away from the most powerful vehicle ever constructed by mankind. On launch day, we couldn't get within three. And the astronauts are going to be on the pad soon for a dry run. When they are in the command module, we can't get this close, either. They may have to eject.

Those engines are twice the height of a man. Millions of pounds of thrust. Engines built by Rocketdyne. The LEM by Grumann. The S-IV-B by Rockwell. That's the third stage. One engine.

You want to know what I want to do when I grow up? This is what I want to do when I grow up. I want to build these. I want to ride in these. I don't know why I love it so much but I do. Can I have your camera? Can I take pictures of this? I know it's just a piece of concrete. It's the launch bunker for the Redstone.

It is the eve of my thirteenth birthday, the Saturday before Easter, Apollo 17 stands at the tower, waiting to be fueled. The last moon rocket. It will be sent up at night a few days from now and I will be back at home. Can we stay for the launch? Is there any way?

I bask in the energy of the presence of the greatest technical achievement that has ever been in the history of human engineering. They built pyramids and Sphynxes and one-hundred ten story office buildings. Hanging gardens in Babylon and the Hoover Dam. But now we are going to the moon. The universe is wide open for exploration. Today the moon, tomorrow, Mars. My grandchildren will be born at a base in Clavius crater. Pan Am is taking orders for the first ticket to the moon, and they will get there just like we saw in that movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, I know they will.

When I was thirteen I felt passion for the first time in my life. Now I knew what it meant to be ecstasy -- to be outside of myself with such focus that I was not conscious of my own safety. From that day forward, I would become an engineer. I would become an explorer of worlds and a conqueror of the mystical religion of technology.

For years I had the pictures from that trip in a Scrapbook I kept under my bed. When I moved away from home in 1977 and I abandoned everything that made me a kid the scrapbook with my picture of the Saturn V disappeared. My mom probably trashed it.

I eventually did become an electrical engineer. It was clear from the time I was seven that I'd never become an astronaut with myopia as bad as mine. And besides, I'm too tall to fit in an Apollo-era space capsule. But I did go to Antarctica, which was my Sea of Tranquillity. I can look at myself in the mirror and say without hesitation, I never lost that passion I had as a kid, and given the chance, despite any risk, I would go to the moon.

Yes I would.

*

On the eve of my forty-sixth birthday, I saw Neil Armstrong. He gave a lecture at our local community college.

Now, thirty six years after his moon walk, he's seventy-four years old. He wears glasses as thick as the ones I wore when I watched him on television as a thirteen year-old. He stutters. He still gets choked up when he talks about standing on the surface of the moon, looking at twenty-three degrees above the horizon and seeing the blue-blue earth hanging in the infinite blackness that is our universe. He leaves no doubt that flubbing man's first words on the moon were a result of his speech patterns, and that if he were to do it again, he'd gladly make the same mistake. "It's just so Neil," would be the way one who knew him would say it. It humanizes the grandeur of the achievement. As it should. Because all our achievement is human.

On the eve of my forty-sixth birthday, I was in the same room as my hero. He's a very affable human being. He's doing his best to remain a simple man. Handles the public spotlight in his down-home, midwestern way. Does speaking engagements to pay the bills.

He's got to be careful about what he says. He can't be overly critical of anything, lest one organization or another seek to use his persona to further their cause. He makes jokes about politicians. He's an environmentalist without being a tree hugger. He's a conservative without the religion.

He avoids answering questions he doesn't want to address in the same manner as a skilled politician. By now he's done so many press conferences and state visits, handling the press is encoded in his DNA. Yes, he flew the LEM to within some few seconds of engine burnout. Yes, Buzz Aldrin took the Catholic sacrement of Holy Communion on the lunar surface. Yes, some people think they see UFOs, and there are strange things out there but they're probably not evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Yes, flying the X-15 to 4000 miles-per-hour was a rush.

The goal of going to Mars is probably attainable, but is more of a pipe-dream than an actual program. Why not go back to the moon, which remains almost entirely unexplored, with an order of magnitude less effort?

In the 1960s, he flew a Gemini space ship around the earth, did mankind's first-ever docking in space, and successfully landed in the ocean to within eye-shot of the carrier, all with the aid of an analog computer whose memory capacity was 2k and whose interface was a single yellow light and a 7 digit display. Imagine what could be done today, he says without saying.

He talks about the dangers of space--the risks that were taken. A single solar flare would have killed them all, subjecting them to five times the lethal dose of ionizing radiation in an hour -- and they were lucky that in all the Apollo missions there was never a solar flare during the flight, even though the sun was at a sunspot maximum during that period. That problem should be addressed before we think about spending two years in transit to and from Mars.

Yes, he has spoken to every man who went to the moon, and the 12 that walked on its surface, and yes, every one internalized the experience and emerged with a heightened sense of spirituality. They all feel more concerned about the fate of the environment as a result. All feel closer to the creator. But Neil is not a man who has ever worn his heart on his sleeve, so he leaves it at that.

Seventy-four years old. Thick glasses and a stutter. He thanks us for our time -- says it's the greatest gift one person can give another -- both at the beginning and end of his talk.

Here is the first human being to set foot on a celestial body other than the earth. Astronaut. Pilot. Explorer.

My kids sort of understand what he means to me, but mostly they don't. I can say that he is one of my heros and I feel like I'm a kid again when they run the reel on the moon landing. "One small step..." the compressed voice comes through the thirty six years, the grainy black-and-white picture we've seen over and over.

And there he is right in front of me. Bowing and smiling. Perhaps it's hard for the people who love me to understand that I would not be me without him.

*

What do kids do these days? Who are their heroes? When they dream of reaching the unattainable heights, where do their minds go?

When I was thirteen I stood on the front lawn of my home in the Chicago suburbs and looked up at the moon in the late afternoon sky and I knew there were men on it at that very moment. Men had traveled in a rocket I had seen, and were traversing the lunar surface, collecting rocks, looking back toward the earth while I looked upward at them.

That doesn't happen anymore and I think there is less hope in the world because of it.

People should have childhoods. Nowadays we expect kids to be adults from the time they can select a channel on the satellite TV. We subject them to "adult situations" as the TV/Movie raiting system calls it. We prosecute them in our courts as if they've the benefit of decades of world experience. We push them to achieve from the time they're born. Here in silicon valley, parents brag about ten-month olds who utter sounds that seem like words. There are two-year olds who recognize printed text. There are three year olds who can tell you the difference between a symphony and a fugue.

Yet we score lower on tests than those of other countries. We're less literate, less capable around numbers.

I had an actual childhood. I was treated like a child, to my chagrin, and the only responsibility I was afforded by my parents was to keep my grades up and keep my siblings from burning down the house when my parents went out with their friends on the occasional weekend evening.

When I was a kid, we were sending men into space and we knew we'd have colonies on Mars someday. We could go as far as we wanted. I knew that was true and to be part of it I would have to excel in my studies and distinguish myself as a student.

Because I knew that all astronauts are smart. They had a mastery of math and the sciences. They were in tip-top physical condition. They served their country and their families. An astronaut was brave. An astronaut was virtuous. You could trust an astronaut with your life savings or your best girlfriend.

When I was a kid that's what a lot of us wanted to be. Virtuous. Brave. A man who lived in service of God and country, and who explored the far reaches of the universe. Someone who designed and worked with machines that could bring you to the brink of incredible terror -- the terror of distant nature, so huge and uncaring that the fear it inspired became awe, became love.

We are all born explorers and whether he likes it or not, every kid has all of life to cross into. From the nothing before birth, a kid has to learn everything adults take for granted. It's the nature of a young person to seek and learn.

If I was young today, what would I hang onto to give me an explorer's hope? What would take my breath away the way Apollo 17 did? Who would I most want to emulate in life?

Even though I know there would be something to replace my desire to become a lunar astronaut, I don't know what it could possibly be.

*

Over the past three months I built a model of Apollo 17. It's five feet tall. It's meant to be flown, so it has a place for a big "G"-class model rocket motor. It has kevlar parachutes.

I got the kit from Apogee Components, which is a one-person company in Colorado. Two-hundred dollars worth of cardboard tubing and paper diagrams came. Three months later I finished it. Though it could have been painted like any of the 10 Saturn Vs, the decals on mine are arranged in the exact configuration of Apollo 17, the very last moon rocket, the one I saw when I was thirteen.

I probably will never fly it. I don't want it broken.

It didn't really fit anywhere in my home, so I brought it to the office. And immediately, my colleagues came into my office to look at it. Most of them are my age. All of them are engineers. The same thing happened to all of them.

They stared at the model and got one version of misty-eyed or another. They each said, "I became an engineer because of this," and, "how come we don't do things like this anymore?" and "I remember when I saw Apollo 15 and the lunar rover," and, "Did you know they had eye charts in the early Mercury space craft because they didn't know if their eyeballs would pop out in the low pressure atmosphere?"

"How long did it take you to build?" one asked me.

"Three months," I said.

And I expected him to ask, "Why?" but he never did. Not one person asked me why I would spend three months of my spare time sanding and painting cardboard tubes to create a 1/70th replica of the moon rocket.

Because it is our first true love. Guys my age learned about falling in love following the space program. We all fell in love first with rockets and space, and later with our spouses.

Thirty six years ago, each of us was going to be a part of it. We read Boy's Life and built plastic models from Revell and Monogram in preparation for the real thing -- and knew without doubt that someday there would be a real thing.

Because when I was a kid, it was possible for an engineer to do anything.

*

Today, on the eve of my birthday, I think about the space program. I have seen an Apollo moon rocket and now Neil Armstrong. I was extremely fortunate to have been born when I was. I was never drafted and taken away to Vietnam. I saw the fall of the Berlin wall. I participated in the explosion of the semiconductor industry, and worked at Intel at the time when microprocessors became a ubiquitious appliance.

I was thinking about the stars. Watching Apollo 11 lifting off the pad with Neil Armstrong himself standing under the screen, Neil and Buzz and Mike floating in space, the first steps on the moon, it reminded me of the big hole we left in the lives of lots of young people by not doing the things that inspired some of us. Yes there were critics. For every mission, there are hundreds who will extol the virtues of staying at home, fixing things here, and things always need fixing. Always. There's no lack of reasons to not do something. Expense. Time. Focus.

Let me say to you, these critics will for now and always remain outside the effort of human advancement. They're there to test you. You will never achieve any of your potential listening to people who advise you to avoid the risks and play it safe and to not waste money with your head in the clouds when there's plenty of work right here at home.

Bullfuckingshit.

It takes a kid to decide a person should go into space, an adult would never do it. Too impractical -- because there's nothing in particular out there. But kids know there's everything in particular there. It takes a kid to decide we should walk on the moon, not because it has a fiscal, religious, social, or political purpose, but just because it's the plain ordinary fucking coolest thing a person could ever do, and the very idea of it is gold to the rest of us. The very idea of it makes us what we are.

I think we're lacking as a nation. I think the lack of a government-sponsored exploration program -- to explore ANYTHING -- makes us berift as a people. We have a gigantic hole where our imaginations should be and we've filled it with the soil of human nature that takes the place of anything we fail to do. We've filled our lack of exploration with fear. We're becoming a society of fear. Fear of terrorism. Fear of disease. Fear of lack of oil. Fear of despots. Fear of traffic accidents. Fear of financial ruin. We are afraid of everything and it's getting worse. Like a cornered animal we're showing our teeth ever more frequently, forgetting the moral obligation we have as the strongest to withdraw from arms. My dad used to tell me I would face his wrath if he caught me striking a girl or a little kid, even when one hit me first, because as the stronger party, I had the obligation to take the punishment and walk away. Revenge is the haven of the weak of spirit, the unimaginative, and the enemies of hope.

Because we no longer explore and face the dangers nature has to offer, we have nothing better to do than to culture our fear of each other, and use our technical might in the pursuit of the destruction of an ever growing list of enemies. And the list grows as our fear grows, and as our fear grows our pain grows, and we find others upon which to exact our revenge.

We need a space program. We need exploration. We need to be able to follow the reality-TV event of the year when man sets down on the moon again. When someone walks across the red plains of Mars. We need human exploration because without it, we are simply ants in a colony, aimless pursuing further existence without the potential to BECOME.

I nearly burst into tears watching the men in Houston leap for joy when they heard the words, "Houston: Tranquility Base, here," because it was an achievement of such grandeur and innocence. The motivation for the space program was all about beating the Communists -- but had absolutely nothing to do with it in the end. In the end it was a couple of guys on the moon, eating communion and flubbing their lines. Short guys who fit in space capsules. Human achievement, despite the cold war.

Something a kid could grab onto and hold for his whole life.

Last night with my own ears I heard Neil Armstrong flub another line -- he said: "Someday I believe we will send unarmed men to Mars. I mean, manned and unarmed vehicles. Well, always unarmed."

But I knew it wasn't a misstep, because he didn't screw up a single sentence the rest of the evening.

I guess if you knew him, you'd have said, "That was so Neil."